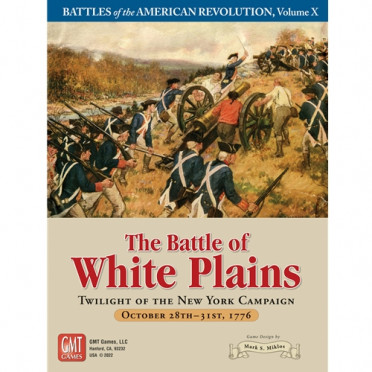

The Battle of White Plains

GMT2213

- English

- From 14 years old

- 2 to 3h

- 2 player(s)

As it unfolded, the Battle of White Plains could rightly be called the Battle of Chatterton Hill. This relatively small affair, which took place on the American right flank on October 28, 1776, was the only overall action between the two protagonists. Some 4,000 British and Hessian troops attacked fewer than 2,000 Americans, with the King's forces ultimately prevailing.

The main armies, however, were huge for the time, with 14,500 Americans facing 13,000 British and Hessians, who were eventually reinforced to 15,400, making this one of the largest concentrations of opposing troops in the war and the largest game in the Battles of the American Revolution series to date. Yet despite this concentration of forces on a front barely three miles wide, the armies remained virtually inactive after the Battle of Chatterton Hill as the British probed the flanks and the Americans improved their defenses.

Washington had chosen a strong position and fortified it with two concentric lines of fieldworks bristling with forty guns. Its flanks were anchored on high hills and secured by the Bronx River to the west and the wilderness swamps to the east. Secure in these positions, Washington welcomed the prospect of a frontal assault on its works.

For his part, General Howe's reluctance to launch a frontal attack was due in part to the fact that he had witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775, the memory of that massacre still fresh in his mind. The weather at White Plains was also a mitigating factor with cold autumn rains falling for much of the week that the armies remained in contact. Finally, Howe's propensity to hesitate when decisive victory was at hand exacerbated plans for a major British assault.

Washington reacted to the loss of Chatterton Hill by initially denying his right. Sensing the growing weight of the British army, he eventually pivoted on a hinge leaving his left where it had begun, on Hatfield Hill, while moving the rest of the line back about two miles to even higher ground in North Castle Heights where he dug new fieldworks. Like two heavyweights maneuvering to shorten the ring, each sought an opening - Howe to push the attack under favorable conditions and Washington to receive the attack on fortified ground of his choosing.

Finally reinforced by Lord Percy with six regiments plus some newly arrived Hessians, and having discovered no viable way around the flanks, General Howe decided to attack Washington head-on on the morning of October 31. He put his men on alert at 5:00 a.m., but the heavy rains of the morning cooled his ardor and the army was again ordered to withdraw.

There was more probing and some long-range artillery fire against the American flanks on November 1, without much consequence. Howe now thought he was facing only an American rear guard in the North Castle Heights lines and saw no point in attacking it, believing that Washington with his main force had already avoided it by marching further north. The armies therefore looked at each other in awe until November 5 and 6, when General Howe decided to turn south to complete the conquest of Manhattan by capturing Fort Washington, which he did successfully on November 16. As Howe turned south, Washington turned north. He divided his forces into three groups. Major General Lee was to protect the New England approaches while Major General Heath was to guard the Hudson Highlands and points north. The commander-in-chief and the rest of the army crossed the Hudson River at Peekskill and marched south through New Jersey to stay between the British in New York and the U.S. Capitol in Philadelphia.

The main armies, however, were huge for the time, with 14,500 Americans facing 13,000 British and Hessians, who were eventually reinforced to 15,400, making this one of the largest concentrations of opposing troops in the war and the largest game in the Battles of the American Revolution series to date. Yet despite this concentration of forces on a front barely three miles wide, the armies remained virtually inactive after the Battle of Chatterton Hill as the British probed the flanks and the Americans improved their defenses.

Washington had chosen a strong position and fortified it with two concentric lines of fieldworks bristling with forty guns. Its flanks were anchored on high hills and secured by the Bronx River to the west and the wilderness swamps to the east. Secure in these positions, Washington welcomed the prospect of a frontal assault on its works.

For his part, General Howe's reluctance to launch a frontal attack was due in part to the fact that he had witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775, the memory of that massacre still fresh in his mind. The weather at White Plains was also a mitigating factor with cold autumn rains falling for much of the week that the armies remained in contact. Finally, Howe's propensity to hesitate when decisive victory was at hand exacerbated plans for a major British assault.

Washington reacted to the loss of Chatterton Hill by initially denying his right. Sensing the growing weight of the British army, he eventually pivoted on a hinge leaving his left where it had begun, on Hatfield Hill, while moving the rest of the line back about two miles to even higher ground in North Castle Heights where he dug new fieldworks. Like two heavyweights maneuvering to shorten the ring, each sought an opening - Howe to push the attack under favorable conditions and Washington to receive the attack on fortified ground of his choosing.

Finally reinforced by Lord Percy with six regiments plus some newly arrived Hessians, and having discovered no viable way around the flanks, General Howe decided to attack Washington head-on on the morning of October 31. He put his men on alert at 5:00 a.m., but the heavy rains of the morning cooled his ardor and the army was again ordered to withdraw.

There was more probing and some long-range artillery fire against the American flanks on November 1, without much consequence. Howe now thought he was facing only an American rear guard in the North Castle Heights lines and saw no point in attacking it, believing that Washington with his main force had already avoided it by marching further north. The armies therefore looked at each other in awe until November 5 and 6, when General Howe decided to turn south to complete the conquest of Manhattan by capturing Fort Washington, which he did successfully on November 16. As Howe turned south, Washington turned north. He divided his forces into three groups. Major General Lee was to protect the New England approaches while Major General Heath was to guard the Hudson Highlands and points north. The commander-in-chief and the rest of the army crossed the Hudson River at Peekskill and marched south through New Jersey to stay between the British in New York and the U.S. Capitol in Philadelphia.

Copyright © 2025 www.philibertnet.com Legals - Privacy Policy - Cookie Preferences - Sitemap